The transcreation map: How to adapt translations for a good user experience

October 28, 2020 / 6 min read

Table of contents

- The changing role of translators

- The current state of machine translation

- Machine translation is a helpful tool, not (yet) a substitute for people

- The importance of translating for the target audience

- What is localisation and transcreation?

- The transcreation map

- Translations based on trust

- Communication is key

- Translators need full context

- Is it really OK to delete information as a translator?

- Summary: A good user experience

- Contact us for transcreation services

In the last few years, many clients have started to ask for transcreation instead of regular translation, which is great. But what exactly is the difference between a translation and a transcreation? And how do the translators know how to adapt and localise a text? At NoA Ignite, we created a transcreation map with our recommended best practices to guide everyone who is involved in creating language versions.

Download a copy of the transcreation map

The changing role of translators

As machine translation continues to make progress, the role of translators has to change too. One way to stay on top of everything is to make sure that we add value that automated translations lack: Making sure that the translated content is fully adapted for the target market for the best possible user experience.

The current state of machine translation

Machine translation tools like Google Translate and Deepl have come such a long way that they give the impression that translation is easy, instant, and free.

In reality, we are still miles away from automatic translation magic. This is easy to illustrate with a couple of examples that Google Translate came up with this summer. The first example is from a text about stand-up paddling (SUP):

Here Google has interpreted “balance” as “credit balance”, so the Swedish translation reads “... and challenge your credit balance on a SUP card”. Sweet, but plain wrong. And let's face it, totally ineffective if you’re trying to interest people in stand-up paddling.

The second example is when Google Translate suggested that I translate “Enjoy yourself on the trails, but respect wildlife and other hikers” to something like “Give yourself pleasure on the trails, but pay respect to wildlife and other hikers.” For those who know Swedish: “Njut av dig själv…” Yikes - you don’t need a dirty mind to read something else into this sentence :)

Of course not all machine translation blunders are as funny as these examples. But even when machine translation is not wrong, it is hardly ever great either. I translate on a weekly if not daily basis and at the moment, it happens maybe once every 6 months that I spot a machine translated sentence that doesn’t need any editing at all.

Machine translation is a helpful tool, not (yet) a substitute for people

The examples above don’t mean that machine translation is useless – on the contrary, it’s becoming more and more helpful for translators. At least for some language pairs and for some types of texts. Only a few years ago, it was mostly a nuisance. But if a translation is going to be used for any commercial purpose, even texts from the most sophisticated program need editing.

There are other reasons why we can't rely on machines just yet. To create a good user experience in multiple languages, we often have to add or remove information from the original. Today's machines are not ready to make such decisions.

The importance of translating for the target audience

In multilingual products, the target audience is different in every market. I remember working on one campaign where the American target group was 25-35 year-old adventurers, while the Scandinavian market targeted couples over 50. And even when the target groups share some characteristics (for example age and interests), they still have different sets of cultural and geographical references and different ways to express themselves.

This is exactly why regular translation doesn’t cut it when a product or website will be launched in several markets. The content is not just there to give the users information. It is there to spark interest, engage users, sell the product and retain customers. And that’s exactly why translated texts need to be localised and transcreated so that they speak the users’ language.

Every language has its own conventions when it comes to sentence length, word order, use of commas, level of formality and other curiosities. If we copy the conventions used in the source language instead of rewriting them according to the conventions in the target language, we end up with a linguistic monster.

What is localisation and transcreation?

Localisation and transcreation have a lot in common, and sometimes the two terms are used interchangeably. Both terms refer to the process of making sure that translated content makes sense and has appeal in each local market where the product will be launched.

The term localisation has been more common within the games and tech industries, whereas transcreation has been more in use within content marketing and for longcopy translations like editorial articles.

Sometimes, localisation refers primarily to changing formal elements like punctuation, date and number formats to local conventions (for example, British English writes numbers as 10,000.00 whereas the Swedish standard is 10 000,00), and transcreation is used to describe texts that have been more heavily adapted in terms of style and content.

In both cases, the translator (or localizer or transcreator or bilingual writer or editor or whatever you prefer to call the person who transform copy for a new market) has to use their judgement to adapt content so that it resonates with their target groups.

The transcreation map

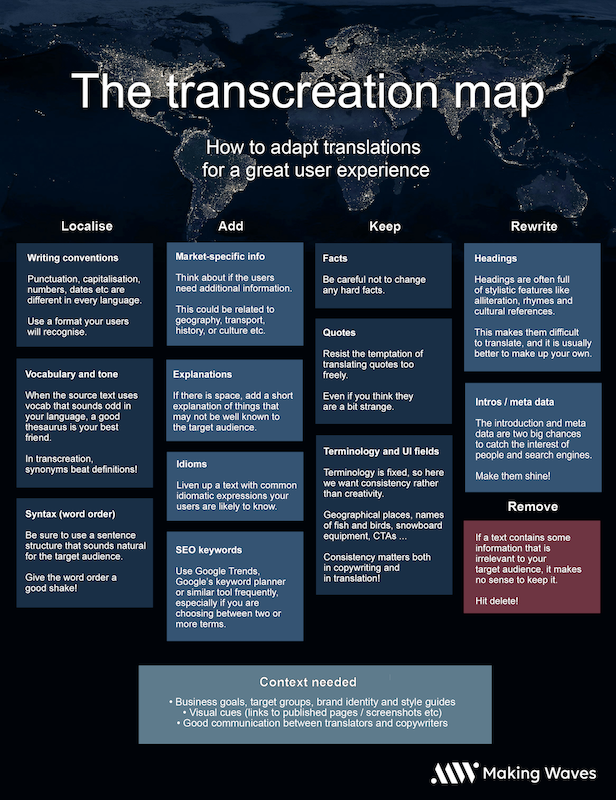

So what kind of changes should translators do? Transcreation usually includes rephrasing sentences and adjusting the style and tone so that it sounds natural and idiomatic. Sometimes, information has to be added or removed. And at the same time, if the translator makes too many changes, it may contradict the original message and the text stops being a translation altogether.

Also, localising translations has to make financial sense. If it takes too long, we might as well start writing original content for all language versions. And if every local market comes up with their own stuff all the time, it will be difficult to maintain a consistent brand story across markets.

So how do translators know what kind of changes to make, without spending too much time on it and without going too far in their localisation efforts? The sweet spot is to find a balance between creativity and accuracy so that the intent of the original text is not lost along the way. This is harder than it sounds.

To help the editors at Making Waves strike the right chords efficiently, we made a transcreation map. The idea is to make it easier for us to transform articles to to different language versions:

Download a copy of the transcreation map

Translations based on trust

The transcreation map requires trust in the people who translate. We have found that it is not beneficial for anyone to spend time checking that a translation is “correct” compared to the original text. The goal is always to create content that works in its own right, not a text that follows the source text too closely. Why would we want them to be the same when they are intended for different markets with different target groups?

Communication is key

Instead, we encourage translators to use their own judgement and adapt the texts as they see fit. For this to work, communication is key. As most of our editors work closely together, we can discuss any thorny translation issues and suggest solutions through a dedicated Slack channel or in weekly meetings. We also work closely with the folks who create the original versions of the text, so we can always ask them if anything is unclear and particularly hard to transcreate.

Translators need full context

Last but not least, it is vital that the translators have all the information they need to be able to do a good job. This means that they should be familiar with the editorial style guide for their language version, with the target groups and with the goals of the clients.

They will also need visual cues. The ideal scenario is that the translators or other language specialist works directly in the design or publishing tool. If this is not an option, they will need screenshots or links to already published content. If this is not an option either, the very last workaround will be a textual description of the intended output.

I recently received an Excel sheet with UI phrases to translate for a client, without any further explanation. I wrote back saying that as an example, there are at least four ways to translate “cancel” into Swedish. Without context, I have 25% chance of getting it right.

Is it really OK to delete information as a translator?

One final thought, as I have the impression that some translators are terrified of making too many changes to the text they are translating: Is it really OK to get rid of something as part of the transcreation process? Yes! Here’s a straightforward example that springs to mind:

A Norwegian client writes a text in English that will be transcreated to numerous languages. In the Swedish version, I will most definitely remove a sentence like “Norway is situated next to Sweden”. Sometimes, certain information is simply obvious to the target group. As transcreators, we always have to ask ourselves, “is this relevant for my target audience?”.

Summary: A good user experience

For multilingual products to make sense to the target audience, content has to be localised or transcreated rather than translated in a traditional sense. To be able to do this, we have to make sure the translators and language specialists have full access to information like business and product goals, editorial style guides and information about the target groups.

It’s all about focusing on a good user experience. Recently, I’ve even started thinking of the process as UX translation rather than transcreation, but that will be the subject of another article!

Contact us for transcreation services

Our content services department transcreates content for digital products in more than 12 languages. If you have a need to localise your website, app or other digital product, feel free to get in touch!

Author

Anja Wedberg

Senior Content Editor

Anja is a Senior Content Editor with a background in translation, marketing and web publishing. She spends most of her spare time fighting, either with new karate moves or with Polish consonant clusters. Check out the rest of her blog articles at medium.com/anja.

Related articles

![A well-crafted prompt doesn’t just work once. It works across teams, channels, and campaigns. It can be tweaked for new use cases and refined based on what performs best.]()

June 27, 2025 / 4 min read

Prompts are marketing assets: how to reuse, and scale them

Prompts aren’t throwaway lines. They’re repeatable, scalable assets that can streamline your marketing your team’s output. Learn how to build a prompt library that delivers.

![Woman using a wheelchair in the office settings]()

June 17, 2025 / 5 min read

What is accessibility and why it matters?

Accessibility ensures everyone — including those with disabilities or limitations — can read, navigate, and engage with your content equally.